——————

“I almost cried.”

– “Why didn’t you?”

——————

I have never seen my dad cry.

I remember once he did but secretly on a very rare occasion while we were watching American History X, just me and him sitting in the living room, waiting for my mum to come home, I must have been seventeen or eighteen and all of my three siblings had moved out already and somehow this movie was on TV that night and because my dad is a serious man and this is a serious movie I thought the two would match.

I did not quite anticipate the explicit brutality that would be displayed in the film, the horrors of white supremacy, that one scene, if you’ve watched the movie, you know exactly what I am talking about, a pavement, a kick, a crack. But the last thing I expected was my dad’s reaction.

„Your dad was completely destroyed last night.“ My mum told me the next morning over breakfast. „It really hit him. What kind of movie were you watching?“ she added with an accusing tone, as if I should have known:„Your dad is a very sensitive man.“

– This was news to me.

The first man that I saw crying was my first boyfriend. I remember it very vividly because I did not handle it well. At all. In fact I acted horribly. At first I wouldn’t say anything, then I would flinch or role my eyes and at some point, I think I am not exactly sure but I might have burst out the words: „Oh my god can you please stop whining!“

There are always moments you’d wish you could rewind and change when it comes to relationships and this is absolutely one of them.

———————

“I almost cried.”

– “Why didn’t you?”

“Well.”

———————

Last year I listened to a talk by Brene Brown on the On Being podcast where she talks about this behaviour that women often display when men cry:

“For men, there’s a really kind of singular, suffocating expectation and that is to not be perceived as weak. So for men, the perception of weakness is often very shaming. When I talk to men what I heard over and over was some variation of, look, my wife, my girlfriend, whomever, they say: share your vulnerability with me, open up, be afraid, but the truth is, they can’t stomach it.

The truth is that, when I’m very vulnerable when I’m in fear when I talk about it openly, it permanently changes the dynamics in our relationship. And when I started sharing this with women or whenever I started interviewing couples, women are like: oh, God, it’s true. I want you to be open and I want there to be intimacy, but I don’t want you to go there.

I’ve come to this belief that, if you show me a woman who can sit with a man in real vulnerability, in deep fear, and be with him in it, I will show you a woman who, A, has done her work and, B, does not derive her power from that man. And if you show me a man who can sit with a woman in deep struggle and vulnerability and not try to fix it, but just hear her and be with her and hold space for it, I’ll show you a guy who’s done his work and a man who doesn’t derive his power from controlling and fixing everything.”

———————

“I almost cried.”

– “Why didn’t you?”

“Well. I remember you said you didn’t like it when men cry.”

———————

In my early twenties, I had the opportunity to be one of the chosen people that got a job as an assistant at the prestigious Burgtheater in Vienna, a theater dubbed in the german-speaking realm as “one of the best”. I had been on Erasmus and by sheer coincidence landed a job for a two-month production of the play The commune directed by Thomas Vinterberg.

There’s one anecdote I always pull out when I talk about how it was to work with him. One evening after rehearsal Vinterberg, one of the actors, and me walked back to the tram station. They were heavily discussing a problem that occurred during rehearsal and me just being a 20-year-old, that constantly felt out of place, I trotted along not really contributing to anything. I might as well not be here, I thought and when the time came and my tram arrived I didn’t feel like interrupting their flow so I just entered it, whispering goodbye but quite sure neither of them had heard it.

The next morning when I was making myself a coffee Vinterberg stood behind me, tapped on my shoulder, and said: “I’m awfully sorry about yesterday about not having said goodbye. You were all of a sudden gone and I guess we were too focused on the discussion. That shouldn’t have happened. I’m sorry.”

There are people who see you even when you don’t see yourself.

“All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone,” wrote the French philosopher Blaise Pascal. Which I think to a degree is true, but I would argue that a lot of other problems stem from a man’s inability to be vulnerable and thus to connect with others. Because most of the time we are not alone in the room. There are others. There are always others. Even when you conceal all your emotions and bottle them up and keep them in your head and pretend you’re all alone in this world. You’re not.

———————

“I almost cried.”

– “Why didn’t you?”

“Well. I remember you said you didn’t like it when men cry.”

– “I said I didn’t handle it well the first time.”

———————

This year Vinterberg won an Oscar for his film Another Round originally titled Druk meaning: drinking yourself into a coma. The film is about four “deprived, white, drunk men” he said in his Oscar speech, who all work as teachers at the same high school.

In one of the first scenes, we see Martin played by the wonderful Mads Mikkelsen sitting at the table in a fancy restaurant, trying to pull it together. It’s his friends Nikolaj’s birthday and the four men talk about how things are at school at the moment, their family lives, how Martin seems to be having trouble with his class: His apathy towards life worries everyone. They persuade him to have a drink even though he refused before because he is driving.

As Martin is chugging down the alcohol a transition is made that is watering his eyes, tears welling up, eyelids flicker, he cannot contain it, cannot hold his own anymore. Only with alcohol as the catalyst, he can reveal himself: He cries and immediately apologises for it: Sorry. He says. As if his tears were an attack.

And I want to tell him, that he shouldn’t be sorry and I wish one of them would get up and hug him and say that but his friends though empathetically looking at him they do what probably most men do in these situations, they diverge the conversation and try to cheer him up and it’s then when I realise how much I have longed to see a man cry on screen. For the sheer reason that his wife isn’t really talking to him, admitting that he is lonely and he doesn’t know what to do. Like a normal person. With emotions.

– Actual male fragility and I want to see it.

As the film goes on and alcohol takes the center stage in the process of the four men letting go of their lives, I do wonder what would happen if these men went to therapy. Or if they actually started talking about their feelings when they’re not drunk. Because you can sense that their friendship is real. They take care of each other, they genuinely care. But they are also trapped in a society that wants them to: man up!

Alcohol is the only love language they know. A language that is slowly drowning them. And we all know these men. They’re our fathers, our grandfathers, our brothers, our teachers, our bosses, our partners, men that rather hide in a dark room than be seen as vulnerable by someone that cares for them. With all the privileges and power that they have been provided by the patriarchy, being a human that is allowed to display the whole range of emotions is somehow not one of them.

-

At the end of Vinterberg’s Oscar speech, he talks about the death of his daughter Ida, dedicating the film to her. She died in a car accident, at the same time when Vinterberg had just started shooting his film. He is very composed as he talks about it, but for a moment he wipes a tear from his cheek, his voice breaks as he mutters: Sorry.

——————

“I almost cried.”

– “Why didn’t you?”

“Well. I remember you said you didn’t like it when men cry.”

– “I said I didn’t handle it well the first time.”

“Yes. You didn’t.”

—————

This morning I asked my dad if he realises that I never saw him cry during my childhood. The question weirdly hovering above us.

Were you sad?

Were you scared?

Were you hurt?

Were you lonely?

Could you feel it?

Could you show it?

I could hear him shifting, changing his tone from formal to funny.

I don’t know, he said. I do sometimes cry when I watch a sad movie.

And we both laugh and I let it go. Change cannot happen overnight. Trust not be built in a minute of compassion when there has been a lifetime of damage. It’s an ongoing conversation. A question at the beginning. A start.

Till then I hold this space.

——————

“I almost cried.”

– “I wish you had.”

——————

ONE THING TO DO

Listen to this beautiful dreamy song by Angel Katarain.

IN CASE YOU MISSED LAST WEEK’S MUSE LETTER ABOUT

self-sabotage and why you should never cut yourself off for others.

“And this is where self-sabotage comes into play because we are cutting ourselves off with these rules. For instance to think that this text has to be anything more than me trying my best to explain something to you that I learned then and also have to re-learn again and again is quite frankly a bit demanding. It should be enough that I tell you right here and right now that: You should never cut yourself off.”

If you are not a Muse Salon Member yet but would love to support this project and be entitled to join the bi-monthly Muse Salon workshops - free for Muse Salon members- and have full access to the archives, you can subscribe for £5 per month. You can cancel anytime.

NEWS

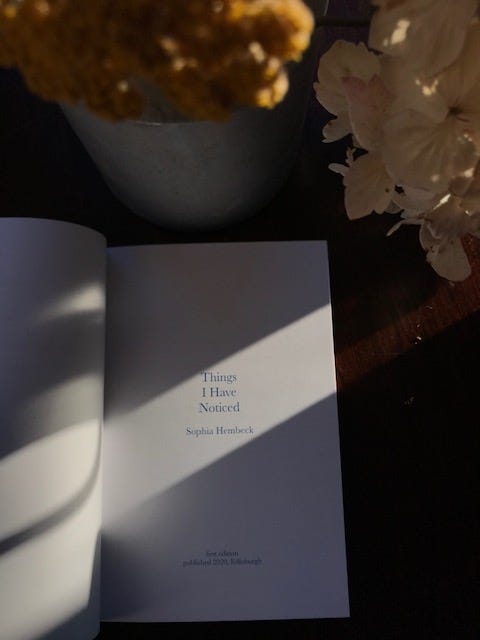

I recently wrote a book of essays called“Things I Have Noticed”. Read a long excerpt here.

“Maybe I had not been looking for the truth, but for a break. For something to be the catalyst of this shit feeling I had been carrying around for months.”

Liked today’s Muse Letter? If you’re feeling generous you can buy me a coffee or share the Muse Letter with a friend or do a shoutout on social media. Support can have many faces.

this is beautiful x